Photomanipulation Of Faces Is Deeply Uncomfortable, And That's Probably What Makes It Art

Photoshopping is a core feature of the InkBlot art style, along with an aversion to colour toner. But even before InkBlot we were photoshopping animal heads onto each other's bodies for fun. I’ve never really considered myself a true visual artist, but upon creation of a dapper ibis in a plum suit, I knew we were on to something. It was the kind of bizarre feeling that only comes from true art, and now the photoshopped images in Authors are a genuine feature of the magazine. Since then I've wrestled with notions of what makes something truly artistic, and the below is what I have so far.

How does it feel, exactly?

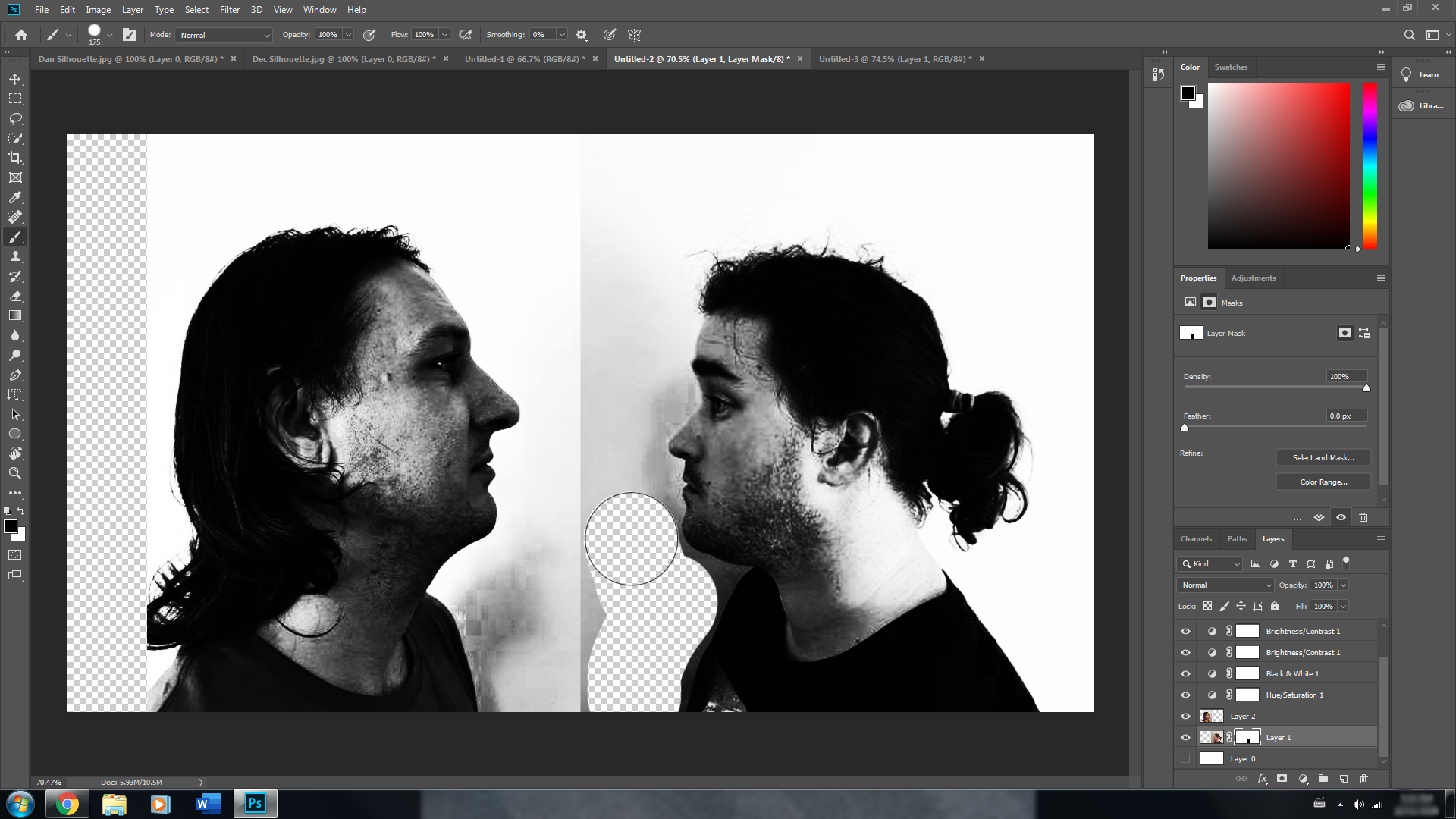

That depends a lot on the context. Historically we worked solely on the faces of others and showed them alongside pieces that were already deeply revealing, so it was difficult to separate the reactions to one from the other. In that context, there’s a recognition of the human element in the image, mixed with an uncertainty of the image as a whole. This produces a kind of pleasant interest borne of a drive to remedy that uncertainty, if only to ascertain how it was produced. But we recently subjected ourselves to this experience while producing the silhouettes for our About section, and that personalises and intensifies it. The result was effective, but the process was a constant struggle between preferencing how it looked and how we looked in it. It's not something I could have done alone because the bias was largely unconscious: I would simply be repelled by something and feel a desire to correct it, though doing so would strip it of its power more generally. When asked more recently, my partner described it as "disconcerting", but at the time we were caught up in a kind of hyperfixation, repeating statements like "[I] didn't realise my throat was like that" (alternatively, I fixated on the size of my nose). We would become convinced the source photos were somehow faulty, because the silhouettes showed details that we ignored in a more realistic image. So closeness seems to matter: so far those more familiar with the subjects have been the most entertained by them, while the subject themselves, as one returning contributor put it, can find "the whole experience...various levels of distressing".

OK, but how is that art?

Well I'm a writer, first and foremost, so my concept of art and its functions comes more or less from literary theory. Russian formalism was a study of poetry which defined art by its difference from the familiar, and the impact that this has on the reader. The crucial function of this defamiliarising is to extend the moment of perception by making the known new again so that we may view it with fresh eyes. But what most concerns me is that art must be evocative, or moving in some way, and so I use theory more as a form of rationalisation after the fact (you know art because you feel it). However, both these constructs require that it be in some ways challenging, as acknowledging the size of my own nose challenged my ego and perception of self, though I would value the social and emotional challenge over the intellectual. We also agree on the why, as they would describe a lack of this effect (an abundance of familiarity) as allowing an individual to function without thought of even their own actions. This then seems like a kind of call to reflection post-deconstruction of unexamined truth (by making things weird, we can question the normal). Applied back to our example, we have: the defamiliarisation of something as familiar to us as our own faces allows a reassessment of something as pivotal as our own image. I'm not sure I will ever again forget just how large my nose is, and so in some small way my self-perception has been forever shifted.

So it's just weird then?

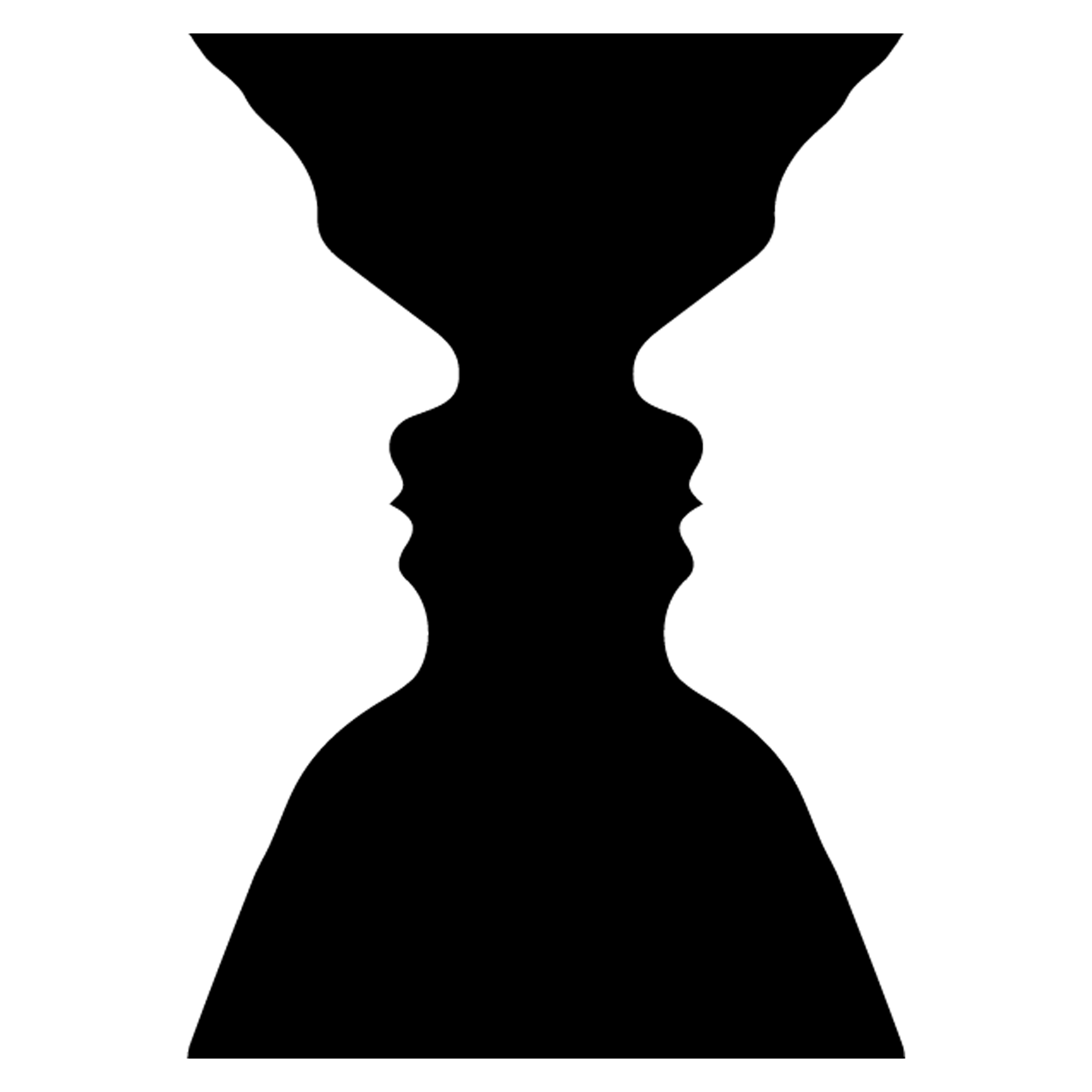

Yes and no. One thing we discovered was the importance of striking the right balance between familiarity and abstraction. Masahiro Mori, a roboticist, discusses the Uncanny Valley with regards to robotic design, potentially best illustrated in their attached graph. Look it up, because it's fascinating, but the lesson for this discussion is how thin the line is between a human-looking other and an other-looking human in our perceptions. In this context, the familiarity came from the source images as representations of genuine humans, a form we're particularly adept at identifying, and the abstraction from their reduction to colourless lines. But the balance was even finer than that: too high a resolution before the trace and it looked like a blacked out photograph, but too low and it was simply a vaguely human shaped blob. This notion of the uncanny (the point between those two images) was historically pinned down by Freud as an uncertainty, but more recently the concept of abjection is used to describe the horror experienced by a breakdown in meaning between what is and isn't the self (in the sense that we identify with other humans as being like us). The purest expression of this is something like gazing at a cadaver, but a more relevant example is the work of Patricia Piccinini (once again: look it up) when combining human and animal forms into something that can't be easily placed into either category. By striking this balance, she produces a range of emotions from repulsion to fascination: one being the desired extension of the moment of perception and the other being an attempt to avoid being drawn into it. By our definitions, that is art, and though we seek a milder, more palatable reaction from audiences, it is effectively the goal with our entire series of InkBlots. Though, it wasn't until recently that we realised just how uncomfortable being the subject of one can be.

In Conclusion

If the goal of art is to make you feel, then anything that produces intense feelings in the artist or the subject is liable to be achieving that goal. Ideally, there would be some appeal to a wider audience and the artist will have a more specific agenda in mind, but these things often follow the first. The hardest part is getting the balance right, but when it works even a black and white outline of a face can do the things that art should do.